Published Jul 17, 2025 | 5:53 PM ⚊ Updated Jul 30, 2025 | 6:31 PM

Tamil Nadu is perhaps the only state that has advanced its library movement into a statewide cultural campaign.

Synopsis: Libraries in Tamil Nadu are more than just repositories of books. In 2010, the iconic Anna Centenary Library opened in Chennai with an investment of ₹172 crore. In 2023, the Kalaignar Centenary Library was inaugurated in Madurai at a cost of ₹150 crore. Similar grand libraries are now planned in Coimbatore, Salem, Trichy, Cuddalore, and Tirunelveli.

In the southwestern corner of Tamil Nadu’s Theni district, the town’s main bus stand is surprisingly calm at 10 am. Some 100 meters away stands a striking building, constructed at a cost of around ₹2 crore: Theni District’s new Library and Knowledge Centre. On its verandah, lie hundreds of bags—a clear sign that their owners are inside, deep in study.

The “Knowledge Centre” is part of a special initiative by the Tamil Nadu government under Chief Minister MK Stalin. Through the Department of Municipal Administration and Water Supply, these centres are designed specifically to support students preparing for competitive exams. They are equipped with newspapers, general and literary books, guides, previous years’ question papers, computers, internet access, and even coaching classes.

The knowledge landscape.

This is the next chapter in Tamil Nadu’s long-standing public library movement.

Inside the library, P Raja, a 27-year-old student, was preparing for the Chartered Accountancy (CA) exam.

“My father is a construction worker,” he told South First. “If I had to attend a private coaching centre, it would cost anywhere between ₹50,000 and ₹1 lakh. But here, I have access to everything—from newspapers to general reading, literature, and a wide range of competitive exam books—for free.”

Typically, Raja arrives at 9 am and studies until 5:30 pm. Like him, hundreds of students treat the library like a second home, bringing lunch with them and leaving only in the evening—just like a regular school day.

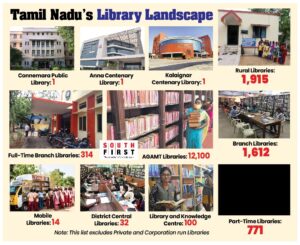

Across Tamil Nadu, the library network is massive. Under the Directorate of Public Libraries, there are 4,661 libraries. The Rural Development and Panchayat Raj Department manages 12,110 Anna Marumalarchi village libraries, and 100 more libraries and Knowledge Centres function under the Municipal Administration and Water Supply Department. That’s a total of 16,871 public libraries—used daily by over 1.5 lakh readers, students, and competitive exam aspirants.

If Tamil Nadu’s population is estimated at 8 crore, that translates to roughly one library for every 4,700 people. This excludes private and corporation department-run libraries.

The Library and Knowledge Centre in Theni.

In addition to these, model hut libraries have also been established in urban areas such as beaches and parks. Such similar setups are seen in Tamil Nadu and Kerala, where political parties have opened compact reading spaces, often in hut-like structures called “Padipagam” stocked with local and international books.

There are also several special libraries in Tamil Nadu having rare materials, such as the Adyar Library and Research Centre; the Government Oriental Manuscripts Library in Chennai; the Roja Muthiah Research Library in Chennai; the Gnanalaya Library in Pudukkottai; the Mahakavi Bharathi Memorial Library in Erode; the Sivagurunathan Tamil Library in Kumbakonam; and the Tamil Manuscript Repository in Virudhachalam.

From the British colonial era to what the DMK now calls the “Dravidian model” of governance, Tamil Nadu’s public library movement has been a landmark success in knowledge democratisation.

Even though colonial rulers may have planted the early seeds of mass education, it is a historical fact that the movement to democratize knowledge truly began only after India’s independence in 1947.

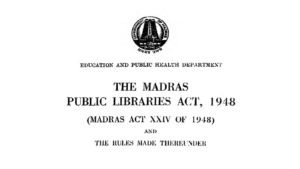

In 1948, under Chief Minister Omandur Ramaswamy Reddiar, the Madras Province became the first in India to pass legislation exclusively for public libraries. The Tamil Nadu Public Libraries Act of 1948, originally called the Madras Public Libraries Act, was a pioneering law that created a formal, state-backed library system.

Tamil Nadu Public Libraries Act, 1948

Before this, libraries in Tamil Nadu were few, elitist, and disorganised. The 1948 Act revolutionised access to knowledge, creating a state-supported network funded by a library cess, with equal focus on rural and urban areas.

The Act provided a clear roadmap: establishing a Directorate of Public Libraries under the School Education Department, setting up libraries at every administrative level from district to village, creating sustained financial support, and making libraries accessible to all.

Later, during the tenure of former Chief Minister M Karunanidhi in 1972, the Directorate of Public Libraries was formally established. It was during these years that libraries began springing up across the state.

“During Kalaignar’s tenure, it was the Dravidian movement that carried the library initiative across Tamil Nadu,” poet and Director of Libraries, Chennai District, S Abdul Hameed, popularly known by his pen name Manushya Puthiran, said.

“The DMK government opened libraries not just in Chennai but across the state. The Dravidian movement from the beginning focused on two key things: Spreading progressive ideas and democratising access to reading. They started reading rooms and ran several journals. The library movement was the next logical step in this mission,” he added.

Libraries in Tamil Nadu are more than just repositories of books. In 2010, the iconic Anna Centenary Library opened in Chennai with an investment of ₹172 crore. In 2023, the Kalaignar Centenary Library was inaugurated in Madurai at a cost of ₹150 crore. Similar grand libraries are now planned in Coimbatore, Salem, Trichy, Cuddalore, and Tirunelveli.

Tamil Nadu is perhaps the only state that has advanced its library movement into a statewide cultural campaign. One notable example is the establishment of 12,100 Anaithu Grama Anna Marumalarchi Thittam (AGAMT) village libraries, launched during Karunanidhi’s 2006–2007 tenure.

In Tamil Nadu, no matter which district you visit, chances are you’ll find a library every 10 kilometres—even in panchayats. Many of these libraries are large enough to house a wide collection of books, including materials suitable for IAS exam preparation.

Thoothukudi Collector K Elambahavath.

“My village is a small one near Orathanadu in Thanjavur district,” Thoothukudi district collector K Elampahavath said. “Just 12 km away, there’s a library in Pattukkottai. Another one is in Orathanadu, also 12 km away. Both are well-equipped with the resources necessary for IAS exam preparation. If someone from a typical rural background wants to study for the civil services, the first place they look for is a library. That’s the very definition of easy access to knowledge. Back when I was studying, we didn’t have online resources like today. Libraries were my only support.”

Elampahavath is not just a successful civil servant shaped by libraries; he also once served as Director of the Directorate of Public Libraries. For him, the library movement represents a “great access to knowledge”—a sentiment echoed by Manushya Puthiran; he firmly believes that the core mission of these libraries is the dissemination of knowledge.

“Books that were once the exclusive domain of privileged communities are now reaching the most marginalised,” Manushya Puthiran said. “That’s the whole point—to democratise access to knowledge.”

“Tamil society has made significant strides in education. Even now, over 50% of students who finish school go on to pursue higher education. We’re number one in the country in this regard. Tamil Nadu is also an industrialised state, which means there’s a steady demand for educated youth and public servants. But not everyone has the financial means to buy books. So even in a developing state like ours, the demand for books is high—and libraries are stepping in to meet that demand,” he elaborated.

From UPSC and TNPSC to other competitive exams, these public libraries offer free books and training. This doesn’t just improve access to knowledge—it provides an opportunity for people from all walks of life to move toward positions of power. Both Manushya Puthiran and Elampahavath believe this is the essence of social justice.

Manushya Puthiran, Chennai District Library Director.

“The idea is to propel students from underprivileged communities toward the power centre. Until now, positions like IAS and IPS have largely been held by people from specific communities. But when someone from a marginalised background enters such roles, they carry with them a deep awareness of social consciousness—and they often act in ways that advance the cause of liberation for their communities. This library movement is, in essence, a social movement for collective progress,” Manushya Puthiran said.

This mission extends from the state’s central libraries, like Connemara, to rural branches. The Public Libraries Department ensures that even the most remote libraries receive at least one weekly magazine, along with multilingual and international journals, and current affairs publications.

At the peak of this initiative stood the Anna Centenary Library and the Kalaignar Centenary Library, both stocked with high-quality publications on science, economics, and various disciplines. Since 2017, with the help of the Tamil Nadu Textbook and Educational Services Corporation, even branch libraries across the state have begun to receive such premium resources—resources that are typically available only at institutions like MIDS or IITs or within private academic circles.

Magazines such as The Economist, The Week, and Economic & Political Weekly are regularly purchased. Moreover, public libraries also subscribe to a wide variety of Tamil periodicals—weekly, fortnightly, and monthly publications—ensuring that knowledge is not confined to English alone, but reaches people in their language.

For Manushya Puthiran, libraries in Tamil Nadu have grown beyond their traditional educational role—they are now transforming into vibrant cultural centres.

Anna Centenary Library Librarian Kamatchi Ramachandran.

Step into the Anna Centenary Library in Chennai or the Kalaignar Centenary Library in Madurai, and you’ll immediately sense that these spaces offer far more than just books. “Each visitor enters a world of their own,” Kamatchi Ramachandran, Librarian at the Anna Centenary Library in Chennai, said.

To make reading easier and more accessible—especially for younger generations—Tamil Nadu’s libraries have adopted a range of tech-driven initiatives. The Anna Centenary Library and the Kalaignar Centenary Library, in particular, have been designed with modern technology to cater to children and youth alike.

“We use technology to translate book abstracts into Tamil, and we translate important articles from newspapers like The Hindu to make them more accessible to students. With AI, we’ve simplified a lot of processes to aid learners. We also use assistive technology to enable visually impaired readers to access books,” she added.

Taking it a step further, libraries have introduced Virtual Reality (VR) tools to engage children. “We use VR to teach them about space, extinct creatures like dinosaurs, and the continents—topics children find fascinating. These VR kits have been provided to district central libraries and flagship institutions like the Anna Centenary and Kalaignar Centenary Libraries,” Ramachandran said.

These libraries also host regular events: Reading campaigns, book clubs, lectures by notable figures, guidance programmes, and summer camps for students.

“Libraries aren’t just about reading books anymore,” Ramachandran said. “We are the only state conducting literary festivals rooted in local riverside civilisations and regional culture, introducing people to grassroots artists and writers.”

While in the past, one might think only of the Jaipur or Kerala Literature Festivals—or The Hindu’s annual lit fest in Tamil Nadu—today, the public library department organises literary festivals in every district. These events bring authors and local communities together, exploring the region’s history and narratives.

No matter how ambitious a vision may be, sustained funding is crucial for execution and longevity. The framers of the Tamil Nadu Public Libraries Act, 1948, foresaw this aspect. They recognised that without a reliable financial model, knowledge democratisation could falter.

The Children’s section at the Kalaignar Centenary Library.

So, when they launched public libraries, they also established a revenue mechanism: A library cess collected alongside property tax. If a property owner paid ₹100 in tax, an additional ₹6 to ₹10 would be collected specifically for libraries, which is 6 to 10%. Local bodies are responsible for collecting this and transferring it to the library department.

Initially, this applied only to urban areas. When the law was extended to rural areas in the 1990s, libraries were included under “civic services,” and rural local bodies were also mandated to collect the library cess.

This created a self-sustaining model, ensuring a steady stream of funds without direct state budget allocations. It worked well for many years—but over time, the actual transfer of cess funds from local bodies to the library department began to decline.

This led to delays in core functions like salary payments and book procurement. In 1982, to address this issue, the government introduced a unified order stating that the state would pay salaries, and local bodies could retain part of the cess to spend on books or infrastructure. However, compliance varied across regions.

Even today, Tamil Nadu remains the only state with such a structured and legislated funding mechanism for libraries. To strengthen it, the State Finance Commission recently recommended that instead of relying on inconsistent transfers from local bodies, the state should directly deduct and allocate the cess amount to the library department.

This has been the practice for the past three fiscal years. “Thanks to this mechanism, a constant flow of funds to the library department has resumed. This year alone, around ₹200 crore has been allocated,” Collector Elampahavath said. “Even when local bodies fall short on remittances, this setup ensures we can procure books and invest in infrastructure.”

This financial framework has sustained Tamil Nadu’s library movement for over 80 years. “You may not immediately see the output of a library, but over time, Tamil Nadu’s top rankings in education and industry owe much to this movement—and to the visionary leaders who nurtured it,” he added.

Looking ahead, the DMK government plans to open Library of Excellence models in every district, including the upcoming Periyar Library in Coimbatore, equipped with state-of-the-art digital resources. These institutions are expected to elevate Tamil society even further in the coming decades.

(Edited by Majnu Babu).